More than medication' needed to treat ADHD

Families of children with ADHD are warning that too often medication is the only option they are offered to manage the condition.

A survey of parents across Scotland found evidence of delays in diagnosing ADHD and inadequate support afterwards.

The Scottish ADHD Coalition also uncovered concerns about inadequate training of school staff.

The Scottish government said medication was offered in accordance with good clinical practice.

It was often accompanied by non-drug treatments such as counselling, it added.

About 5% of schoolchildren have ADHD, a neuro-developmental condition which causes hyperactivity, impulsiveness and inattention.

However, only 1% (9,000) children are known to have the condition north of the border. The Scottish ADHD Coalition believes it is under-diagnosed in many areas.

And in its latest report on ADHD services in Scotland, it raises concerns of an over-reliance on medication in treating the condition.

In a survey of more than 200 parents, 93% said their child had been prescribed medication for their condition and it was helpful.

But in many cases it was the only treatment offered. The survey also found:

- Almost two third (63%) of parents were offered no training to help them manage their child's condition.

- Almost half (41%) were given no written information about ADHD.

- Around 15% said they had received psychological input.

Geraldine Mynors, the coalition's chairwoman, said many children could benefit from more support to address a complex range of difficulties.

"The voices of parents coming through this survey are very clear: there is an over-reliance on medication as the only treatment available to manage ADHD," she said.

"Excellent parent training programmes such as Parents Inc, developed by NHS Fife, are all too rarely available to give parents the long term skills that they need".

'Life is very fast'

Avril Sinclair set up the Brighter Days support group for families living with ADHD in Livingston, after two of her four children were diagnosed with the condition.

"Life is very fast," she said. "We're always on the go. We try to keep to a routine but it's difficult, it's got a lot of challenges."

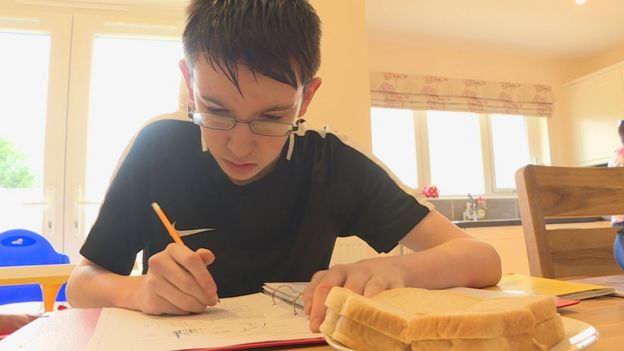

Her eldest son, Reece, was seven when he was diagnosed with ADHD after experiencing problems at school.

She said he benefited from medication as well as a range of specialist help, including play therapy.

When his younger brother Ryan was diagnosed with the same condition, Ms Sinclair said the family decided not to give the youngster medication.

She said her experience of dealing with Reece means she knows how to cope with Ryan's condition.

"Until we find that he's fallen behind at school or we are not able to cope will I look at medication," she said.

But that decision means she has not been offered any additional support to deal with Ryan's ADHD.

She said she believed parents whose children come off medication find it more difficult to access extra support.

The report, Attending to Parents: Children's ADHD Services in Scotland 2018,outlined the positive work carried out by the Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS).

But it found that many families had long waits for both diagnoses and CAMHS appointments, where some felt staff were over-stretched.

And some parents told the coalition that, when they refused medication for their child, CAMHS quickly discharged them, making it harder for them to obtain further support.

Problems in school were also highlighted in the report, which revealed that only a quarter of parents (26%) believed their child's teachers had a good understanding of ADHD.

About 5% of respondents said their child had been permanently excluded from school, while a third (33%) said their child had been temporarily suspended at least once.

The report found a perception among parents that access to support for learning staff to help classroom teachers was jeopardised by staff and funding cuts.

Lorna Redford, a trustee of the coalition, said: "The survey findings reflect what we hear from parents all the time.

"It is imperative that school staff are recruited in sufficient numbers and trained about ADHD to ensure our children and young people receive the same educational opportunities as their non-ADHD peers.

"This modest and realistic target would reap huge rewards in the mental health, quality of life and societal outcomes for sufferers."

The Scottish government said it took the mental health of young people "very seriously".

Mental Health Minister Maureen Watt said: "That is why we have doubled the number of child and adolescent mental health service psychology posts in recent years, and we're investing an extra £150m in mental health over five years.

"Drugs for ADHD are routinely prescribed in line with good clinical practice, including on-going supervision by health professionals to ensure patients only remain on them as long as appropriate.

"They are often used alongside treatments such as counselling or psychological therapies provided locally.

"Early intervention and prevention are the cornerstone of our approach to mental health and wellbeing."

What is ADHD?

- It is a neuro-developmental condition, with symptoms including inattention, impulsivity and hyperactivity.

- ADHD is caused by a mix of factors, including environment and early childhood experiences but it strongly hereditary.

- Symptoms are apparent in early childhood and for most people continue into adulthood.

- It rarely exists on its own and is associated with autism, dyslexia, dyspraxia, sensory processing disorders and tic disorder.

- It can lead to problems including poor academic achievement, unemployment, criminality, and drug and alcohol dependency.

Source: Scottish ADHD Coalition