|

| SENIOR LECTURER, LIONEL BAILLY |

Stimulant medication for the treatment of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: evidence-b(i)ased practice?

Lionel Bailly, Senior Lecturer in Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Honorary Consultant

NEMHP NHS Trust, Royal Free and UCL Medical School, Wolfson Building, 48 Riding House Street, London W1N 8AA, e-mail: rejulba@ucl.ac.uk

Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and its pharmacological treatment remain the objects of intense controversy.

The conflict reaches far beyond the area of scientific debate. An article on ‘behavioural syndromes’, published in The Times on 28 July 2003, was headlined: ‘Hyperactive? Just go to a park and climb a tree’. An internet search will produce equal numbers of sites warning either that the prescription of stimulant medication is a denial of children’s human rights, or that not prescribing stimulant to an ADHD child denies their right to treatment.

In this age of evidence-based medicine, what is the evidence guiding professionals?

Serious scrutiny shows that numerous ambiguities regarding this condition and its treatment remain.

Is ADHD an illness?

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder is an operationally defined concept which is built on a series of behaviours, none of which is specific (contrary to phobias, obsessions, post-traumatic stress disorder, panic attacks, depression, autism, Tourette syndrome, etc.). There is therefore much room for interpretation of these behaviours, and clinicians with opposing views would probably agree only on the most serious cases. In addition, the diagnostic process depends heavily upon information from third parties (parents and teachers), which gives rise to questions about the neutrality of these informants in the face of a clearly difficult child (but one who does not necessarily have ADHD). The diagnostic process is sufficiently controversial for the pharmaceutical industry to post the following warnings to customers on their websites:

‘Specific etiology of this syndrome [ADHD] is unknown and there is no single diagnostic test... The diagnosis must be based upon a complete history and evaluation of the child and not solely on the presence of the required number of DSM-IV characteristics’ (Adderall website; Shire US, 2004: p.1).

‘Specific etiology of this syndrome is unknown, and there is no single diagnostic test...Characteristicscommonly reported include: chronic history of short attention span, distractibility, emotional lability, impulsivity, and moderate-to-severe hyperactivity.. .The diagnosis must be based upon a complete history and evaluation of the child and not solely on the presence of one or more of these characteristics’ (Ritalin website; Novartis Pharmaceuticals, 2004: p. 2).

Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder without attention deficit?

The name ADHD suggests an impairment of attention in at least two of its subtypes (predominantly inattentive and combined), but in clinical practice attention as such is rarely formally assessed in children with ADHD. In a recent study, Koschack et al (2003) assessed the attentional functions of control children and those with ADHD on a computer-driven battery of neuropsychological tests. Their findings show that according to normative data, ‘most ADHD subjects performed on all attentional measures within the normal range’ (Koschack et al, 2003). Comparisons with the control group revealed that ‘ADHD subjects reacted faster on all attentional tests and performed with significantly fewer errors on the Divided Attention test’ (Koschack et al, 2003). These findings would question the appropriateness of the ‘attention deficit’ in ADHD.

Non-ADHD causes of hyperkinetic behaviour

Not all children with hyperkinetic behaviour have ADHD. Many other conditions and situations may lead to ADHD-like symptoms.

Sleep disturbances

In a study on sleep and neurobehavioural characteristics of 5- to 7-year-old children with symptoms of ADHD reported by a parent, O’Brien et al (2003) reported that sleep-disordered breathing can lead to mild ADHD-like behaviour ‘that can be readily misperceived and potentially delay the diagnosis and appropriate treatment’. Not sleeping enough is also a well-known non-medical cause of agitation in children, and if the clinician is unaware of the lack of sleep a child can be wrongly diagnosed with ADHD on the basis of school reports and parental statements.

Side-effects of ß-stimulants

Bronchodilator medication prescribed for asthma has numerous behavioural side effects. In a 12-week double-blind trial of Ventolin in 104 children between the ages of 4 and 11 years, the drug manufacturer, GloxoSmithKline, reported that nervousness was present in 1% of the children, agitation in 1%, hyperactivity in 1% and aggressive behaviour in 1% (http://us.gsk.com/products/assets/us_ventolin.pdf). A child with one or more of these side-effects might be wrongly diagnosed with ADHD. In addition, if these side-effects occur during the child’s formative first years, the symptoms can become habitual behaviours that are difficult to change even after medication has been discontinued.

Hearing impairment

Data from a large multipurpose birth cohort study show that hyperactive and inattentive behavioural problems were evident in children with otitis media (Bennett & Haggard, 1999; Bennett et al, 2001). They can persist into late childhood and the early teens (as late as 15 years) (Bennett et al, 2001).

Behavioural difficulties and bereavement

Some ADHD-like symptoms can be encountered as a consequence of complicated bereavement and could wrongly lead to the diagnosis of ADHD if the professional assessing the child is not aware of the loss. In a review of childhood bereavement following parental death, Dowdney (2000) reported that non-specific emotional and behavioural difficulties among children are often reported by the surviving parents and the bereaved children themselves. Among other behavioural difficulties, such children can display hyperactivity and temper tantrums. Hutton and Bradley (1994), in their study of the effects of sudden infant death on bereaved siblings, found that children between the ages of 4 and 11 years who had lost a sibling to cot death showed significantly more behavioural problems (as reported by their mother) than a matched comparison group. Fifteen individual items of the Child Behavior Checklist were more frequent in the bereaved group. Among these 15 items the following 8 are commonly encountered in children with ADHD: ‘is nervous, highstrung; easily jealous; destroys own things; restless, hyperactive: unusually loud; demands a lot of attention; gets teased a lot; can’t concentrate’ (Hutton & Bradley, 1994).

Manic symptoms

Significant debate exists on whether early-onset bipolar disorder is mistakenly diagnosed as ADHD or conduct disorder (CD). In a review of the literature Kim and Miklowitz (2002) found that ‘Reliable and accurate diagnoses can be made despite the symptom overlap of bipolar disorder with ADHD and CD’. However, this symptom overlap may lead to the erroneous diagnosis of ADHD in manic children.

Child abuse

Among the symptoms and signs of physical abuse listed in the Royal College of Psychiatrists’ factsheet Child Abuse and Neglect: the Emotional Effects, are: ‘aggressive or abusive, unable to concentrate, underachieving at school, having temper tantrums and behaving thoughtlessly, truanting from school’ (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2004a). An unsuspecting professional can wrongly attribute these behavioural symptoms to ADHD. It is therefore important that physicians ‘keep their eyes open to behaviours that signal distress’ (Gushurst, 2003) and do not systematically attribute behavioural difficulties to neurodevelopmental causes.

Inadequate parenting

In an article on the diagnosis of ADHD in pre-school children, Blackman (1999) points out that ‘environmental stressors, inadequate parenting skills can mimic ADHD’. In its factsheet for parents and teachers, The Restless and Excitable Child, the Royal College of Psychiatrists lists among the factors which can make children hyperactive: troubled parents who pay little attention to their children or set no clear rules. The message to the parents is pragmatic: ‘if you have never said what is allowed and what is not, children may simply learn they can get away with being noisy and boisterous’ (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2004b).

The mode of therapeutic action of stimulant medication in ADHD is unknown

As the makers of two of the most prescribed stimulants for the treatment of ADHD point out, amphetamines are non-catecholamine sympathomimetic amines with central nervous system stimulant activity whose

‘mode of therapeutic action in Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is not known’ (Adderall website; Shire US, 2004: p.1).

‘The mode of action in man is not completely understood’

but Ritalin

‘presumably activates the brain stem arousal system and cortex to produce its stimulant effect. There is neither specific evidence which clearly establishes the mechanism whereby Ritalin produces its mental and behavioral effects in children, nor conclusive evidence regarding how these effects relate to the condition of the central nervous system’ (Ritalin website; Novartis Pharmaceuticals, 2004: p.1).

Little is known of the long-term effectiveness of stimulant treatment of ADHD

Again the pharmaceutical industry warns us:

‘The effectiveness of ADDERALL XR for long-term use, i.e., for more than 3 weeks... has not been systematically evaluated in controlled trials.Therefore, the physician who elects to use ADDERALL XR for extended periods should periodically reevaluate the long-term usefulness of the drug’ (Shire US, 2004: p.1)

‘Sufficient data on safety and efficacy of long-term use of Ritalin in children are not yet available... Long-term effects of Ritalin in children have not been well established’ (Novartis Pharmaceuticals, 2004, pp. 3-4)

Stimulant medication is not a specific treatment for ADHD

Rapoport et al (1980) studied the cognitive and behavioural effects of dextroamphetamine in boys with hyperactive behaviour and control boys and men. In a superb piece of research using a double-blind drug versus placebo with crossover methodology, they examined the effects of a single dose of dextroamphetamine sulphate on motor activity, vigilance, learning, and mood in three groups: prepubertal boys with hyperactive behaviour, control prepubertal boys and control men of college age. After taking the stimulant drug ‘both groups of hyperactive and non-hyperactive boys and men showed decreased motor activity, increased vigilance and improvement on a learning task’. ‘While there were some quantitative differences in drug effects on motor activity and vigilance between these different groups, stimulants appear to act similarly on normal and hyperactive children and adults’. Stimulant medication appears to decrease motor activity and increase vigilance of any child and therefore cannot be used as a form of diagnostic test: clinicians cannot say the child has ADHD because stimulant medication calms them down.

After taking the stimulant the men reported euphoria. The boys reported only feeling ‘tired’ or ‘different’. It is not clear whether this difference in effect on mood between adults and children was due to ‘differing experience with drugs, ability to report affect or pharmacologic age-related effect’ (Rapoport et al, 1980). Considering the drug’s potential for addiction, the possibility of an age-related effect is worrying, because it would mean that in their teens, youngsters treated with stimulant would start to experience euphoria.

Risk of addiction and misuse

Members of the Community Epidemiology Work Group of the National Institute for Drug Abuse (NIDA) in the USA made the following information public at their June 2000 meeting:

‘The abuse of methylphenidate has been reported in Baltimore, mostly among middle and high school students; Boston, especially among middle and upper-middle class communities: Detroit; Minneapolis/St Paul; Phoenix; and Texas.When abused, methylphenidate tablets are often used orally or crushed and used intranasally. Some users inject methylphenidate (this is referred to as "west coast"). Also, some mix it with heroin (a "speedball") or in combination with both cocaine and heroin for a more potent effect’ (National Institute for Drug Abuse Community Epidemiology Work Group, 2000: p. 97).

In County Durham, police officers investigating the use of Ritalin found that 30 out of 300 pupils in a comprehensive school were using the drug illicitly. The school price of a tablet was 50p to £1.50 (The Times, 28 July 2003: p. 3).

Influence of advertising

The prescription market for the treatment of ADHD is evaluated at nearly $2 billion in yearly sales, according to IMS Health, a pharmaceutical research and consultancy firm. The competition for a slice of this market is intense, with pharmaceutical companies struggling to keep the lead.

These companies use aggressive marketing techniques to promote their drugs and their reasons are not always purely altruistic. The example of atomoxetine (Strattera) marketed as a non-stimulant drug is particularly interesting. Strattera was introduced in the USA in January 2003 and by June had grabbed 12% of the nearly $2-billion-a-year prescription market. In the first 6 months after Strattera’s introduction, market leader Concerta XL’s prescription share fell from 26% to 22.7%, and Adderall XR from 22.6% to 20.9%, according to IMS Health. Bert Hazlett, an industry analyst with SunTrust Robinson Humphrey (http://www.miami.com/mld/miamiherald/business/6709174.htm) attributes some of Strattera’s rapid growth in sales to ‘Lilly’s expertise in marketing drugs for the central nervous system, gleaned by years of promoting Prozac, its blockbuster antidepressant’. He adds that ‘Strattera is a key pillar in strengthening Lilly’s sales and earnings, which plummeted when it lost the Prozac patent in August 2001’.

Advertising campaigns promote not only drugs but also sometimes the disorder itself: ‘We have to raise awareness of the disease before promoting a brand’, said Lilly spokesman David Shaffer (http://www.miami.com/mld/miamiherald/business/6709174.htm). How much doctors and parents are influenced by the sheer pressure of advertising rather than by medical information remains a crucial but unanswered question.

Conclusion

Depending on a clinician’s interpretation of the available scientific evidence one may conclude that: ADHD is a commonly diagnosed behavioural disorder of childhood for which studies, including randomised clinical trials, have established the efficacy of stimulant drugs in alleviating ADHD symptoms, or that, ADHD is an operationally defined disorder built on a series of non-specific behaviours of which specific aetiology is unknown and for which there is no single diagnostic test.

Contrary to what the name of the disorder suggests, attention processes are rarely impaired. Numerous environmental and emotional stressors can lead to ADHD-like symptoms in children. The mode of therapeutic action of stimulant medication in ADHD is unknown and little is known about its long-term effectiveness. Stimulant medication is not a specific treatment of ADHD and appears to act similarly on children and adults with and without hyperactive behaviour by decreasing motor activity, increasing vigilance and improving performance at a learning task. The clinical response to stimulant medication cannot be used as a form of diagnostic test. The risk of addiction and misuse is not negligible and illicit use of methylphenidate has been reported in UK schools. It is possible that prescription practices in the treatment of ADHD are influenced by the sheer pressure of advertising.

References

BENNETT, K. & HAGGARD, M. (1999) Behaviour and cognitive outcomes from middle ear disease. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 80, 28 -35.[Abstract/Free Full Text]

BENNETT, K., HAGGARD, M., SILVA, P., et al (2001) Behaviour and developmental effects of otitis media with effusioninto the teens.Archives of Disease in Childhood, 85, 91 -95.[Abstract/Free Full Text]

BLACKMAN, J. (1999) Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in preschoolers. Does it exist and should we treat it? Pediatric Clinics of North America, 46, 1011 -1025.[CrossRef][Medline]

DOWDNEY, L. (2000) Childhood bereavement following parental death. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 41, 819 -830.[CrossRef][Medline] GUSHURST, C. (2003) Child abuse: Behavioral aspects and other associated problems. Pediatric Clinics of North America, 50, 919 -938.[CrossRef][Medline]

HUTTON, C. & BRADLEY, B. (1994) Effects of sudden infant death on bereaved siblings: a comparative study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 35, 723 -732.[CrossRef]

KIM, E. & MIKLOWITZ, D. (2002) Childhood mania, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and conduct disorder: a critical review of diagnostic dilemmas. Bipolar Disorders, 4, 215-225.[CrossRef][Medline]

KOSCHACK, J., KUNERT, H., DERICHS, G., et al (2003) Impaired and enhanced attentional function in children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Psychological Medicine, 33, 481 -489.[CrossRef][Medline]

NATIONAL INSTITUTE FOR DRUG ABUSE COMMUNITY EPIDEMIOLOGY WORK GROUP (2000) Epidemiologic Trends in Drug Abuse, Volume 1. Highlights and Executive Summary. June 2000. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health (available at http://www.drugabuse.gov/pdf/cewg/cewg600.pdf).

NOVARTIS PHARMACEUTICALS (2004) Ritalin. East Hanover, NJ: Novartis Pharmaceuticals (available at http://www.pharma.us.novartis.com/product/pi/pdf/ritalin_ritalin-sr.pdf).

O’BRIEN, L., HOLBROOK, C., MERVIS, C., et al (2003) Sleep and neurobehavioral characteristics of 5- to 7-year-old children with parentally reported symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics, 111, 554 -563.[Abstract/Free Full Text]

RAPOPORT, J., BUCHSBAUM, M., WEINGARTNER, H., et al (1980) Dextroamphetamine.

Its cognitive and behavioral effects in normal and hyperactive boys and normal men. Archives of General Psychiatry, 37, 933 -941.[Abstract/Free Full Text]

ROYAL COLLEGE OF PSYCHIATRISTS (2004a) Child and abuse and neglect: the emotional effects. In Mental Health and Growing Up (3rd edn) (eds G. Rose & A.York), p.19. London: Royal College of Psychiatrists (available at http://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/info/mhgu/newmhgu19.htm).

ROYAL COLLEGE OF PSYCHIATRISTS (2004b) The restless and excitable child. In Mental Health and Growing Up (3rd edn) (eds G. Rose & A.York), p.1. London: Royal College of Psychiatrists (available at http://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/info/mhgu/newmhgu1.htm).

SHIRE US (2004) Adderall XR. Prescribing Information. Newport, KY: Shire US (available at http://www.adderallxr.com/pdf/prescribing_information.pdf).

Related Articles

MTA Study Conclusion

“We had thought that children medicated longer would have

better outcomes. That didn’t happen to be the case. There

were no beneficial effects, none. In the short term,

[medication] will help the child behave better, in the long run

it won’t. And that information should be made very clear to

parents.”

--MTA Investigator William Pelham, University at Buffalo

Daily Telegraph, “ADHD drugs could stunt growth, “ Nov. 12, 2007.

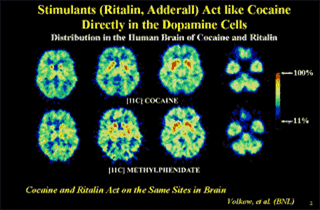

Long-Term Risks With Stimulants(Power Point Slide)

• Desensitized brain-reward system?

• Increased risk of addiction?

• Conversion to bipolar diagnosis: 10%

to 25% now convert

Source: “Bolla,” The neuropsychiatry of chronic cocaine abuse,” J of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 10 (1998):280-9.

Castner, “Long-lasting psychotomimetic consequences of repeated low-dose amphetamine exposure in rhesus monkeys,”

Neuropsychopharmacology 20 (1999):10-28. Carlezon, “Enduring behavioral effects of early exposure to methylphenidate in rats,”

Biological Psychiatry 54 (2003):1330-37. Biederman, “Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and juvenile mania,” J of the American

Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 35 (1996):997-1008.